08 Sep In the company of Peggy Angus

We haven’t been in touch for a while because of the cognitive overload produced by being able to associate freely with people of our choosing in whatever circumstances we consider desirable. We had not remembered that socialising was so exhausting. And we don’t mean that we’re banqueting or anything: just a cup of tea in the company of a friend seems to be enough to fry the neural circuitry for a few days. What a good thing the lockdowns are over. (Is it safe to type those words, or is it positively inviting catastrophe?) If the restrictions had gone on much longer we might all have been permanently transformed into monosyllabic ungroomed pyjama-wearing hermits. In our family we affectionately use the excellent Icelandic term eyjarskeggi to denote people of this type. The literal translation is ‘island-bearded one’, based on the observation that people who live on islands tend to have beards, but it generally denotes the wild and woolly, and perhaps slightly unhinged, demeanour of those who don’t get out enough.

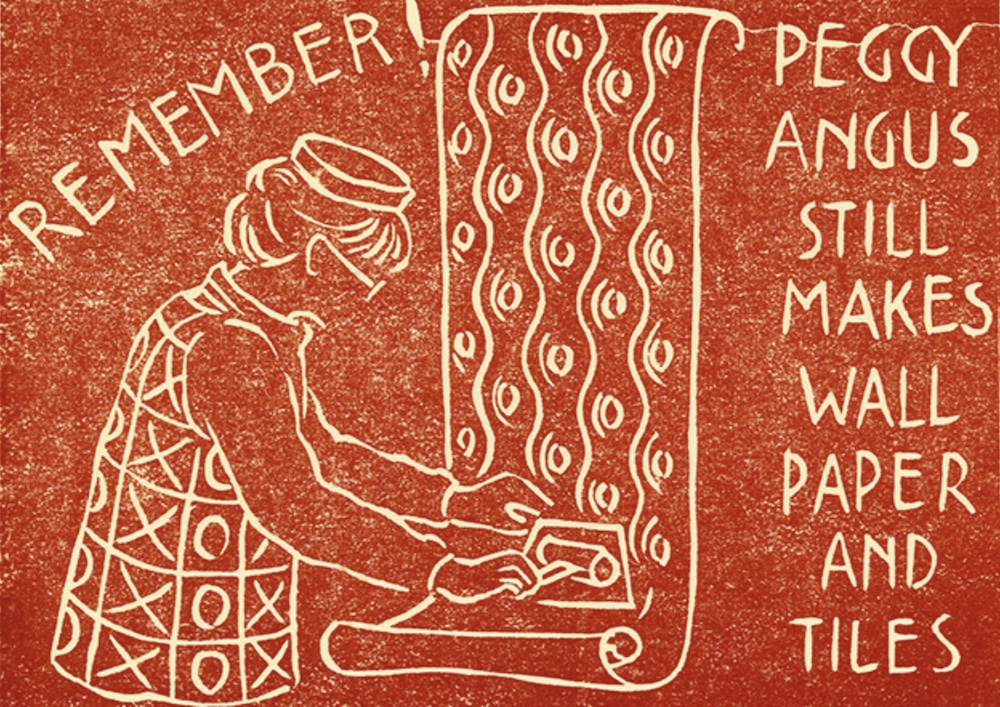

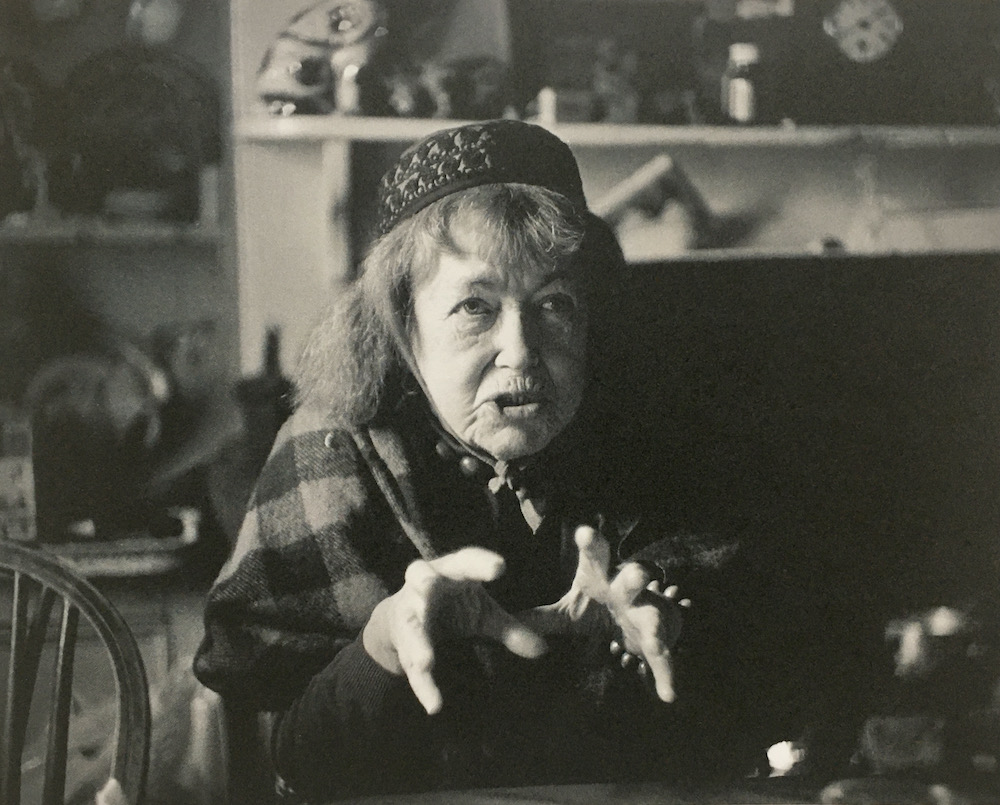

Peggy Angus at Furlongs telling the story of the teeny tiny woman, photographed by James Ravilious.

Peggy Angus, from what we’ve read and heard about her, seems to have been very wild and woolly indeed, but this was clearly not brought on by an excess of solitude. She was highly gregarious as well as hugely eccentric; larger than life and filled with energy; a vital creative force in her own right and an inspirer of others; direct to the point of rudeness and an all-round awkward customer. For many years she presided over Furlongs, an isolated cottage on the Sussex Downs, which acted as an informal artists’ community of a Bohemianism and primitiveness (the lack of modern conveniences was total and legendary) that easily outdid nearby Charleston, home of Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant. In the early days of Angus’s tenancy, before the war, Eric Ravilious and Tirzah Garwood and other friends from her Royal College of Art days were regular visitors. Later on the many visitors included not just friends and fellow artists but old students from her teaching days and the children and grandchildren of friends who were roped into the business of hand-printing her wallpapers.

Enamel Jug and Chamber Pots in the scullery at Furlongs, photographed by Louis Ullman.

Olive Cook’s memory of her first visit describes what seems to have been a typical Furlongs scene. The second she arrived she was caught up in a whirl of congenial activity. Somewhere a new-born lamb was baaing. A young woman was making a collage on the kitchen table and two other young people were constructing an abstract sculpture out in the garden in the bitter cold. Peggy was in the chaotic scullery trying to make order and kettles were boiling on the hob but no preparations for lunch were to be seen. ‘The walls were covered with patterned papers beautifully setting off the numbers of pictures on them and a cupboard was boldly decorated with geometric designs. Tirzah was getting a sketchbook out of the string bag she was carrying. I decided to draw the kettles. Edwin drew a cat. I forgot about lunch and was conscious of a marvellous feeling of not being a guest, of being at home… Then suddenly everyone lent a hand at preparing lunch and soon we were crowding round the table for a splendid time of conversation and conviviality. This was typical of many, many visits to Furlongs: always there was something inventive going on and there one always met dear friends.’

Olive Cook and Peggy Angus on the Downs above Furlongs, with painted tents in the distance. Photographed by Edwin Smith.

Reading about Peggy Angus over the course of the past year, we have all felt a great longing to have been one of the girls she taught at North London Collegiate, where she was head of art for many years. She was clearly an inspired teacher as well as a headmistress’s nightmare, reigning over an independent artistic fiefdom and filled with bold ideas for projects, experiments and decorations that generally livened up this rather straight-laced and extremely academic institution and occasionally threatened the integrity of the school buildings. The syllabus was of her own devising and spanned the entire seven years of a girl’s time at the school, starting off in the first year with Magic Art, a primitive celebration of life, and proceeding chronologically up to contemporary art in the last year of the sixth form. (The year I like the sound of best was the second year, Gothic, when the girls worked on medieval decorations and heraldry, experimented with counterchange, and drew fantastic beasts.) During the course of these years the girls seem to have collectively decorated and serially redecorated the entire fabric of the school, including stairs, corridors, main hall, dining hall and ceilings.

Peggy Angus’s philosophy was one of art as an integral part of life, the process by which one recorded and decorated, and thereby sanctified, the spaces one inhabited and the furniture and utensils and clothing one used. On a trip to Bali late in her life she wrote of the richness of the artistic life she found there, where all made daily offerings by hand — woven charms, carvings, figurines and cakes — as a spiritual exercise. ‘Ideally art is NOT for sale,’ she wrote. ‘Like love it is freely given…fashioned with loving devotion, unstintingly, profligately — for a brief occasion — a passing prayer — not to be preserved and used again or retrieved and sold… How marvellous in this materialistic age for folk to be so profligate with expressions of the spirit as to make ART TO BURN. What confidence in the limitless flow of their creative energy. What real wealth.’

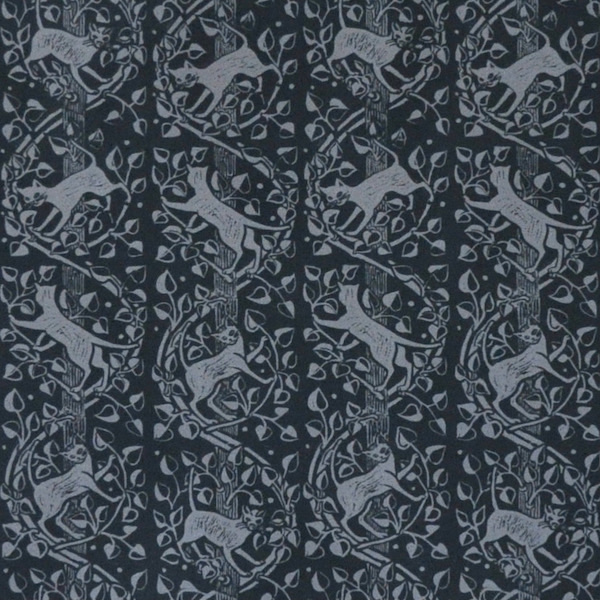

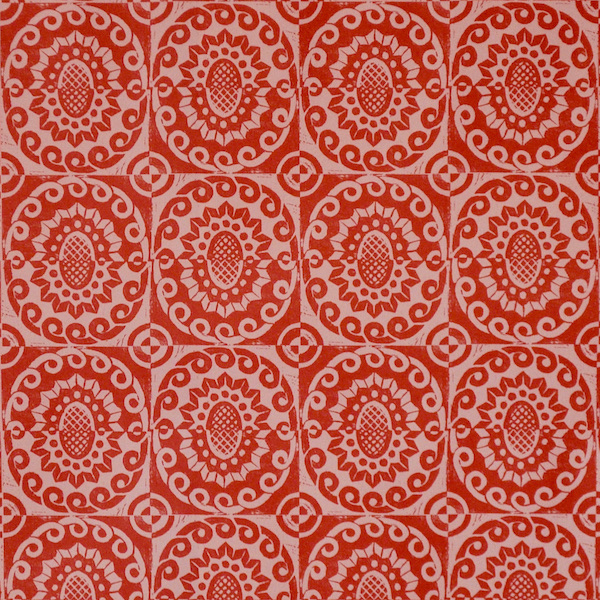

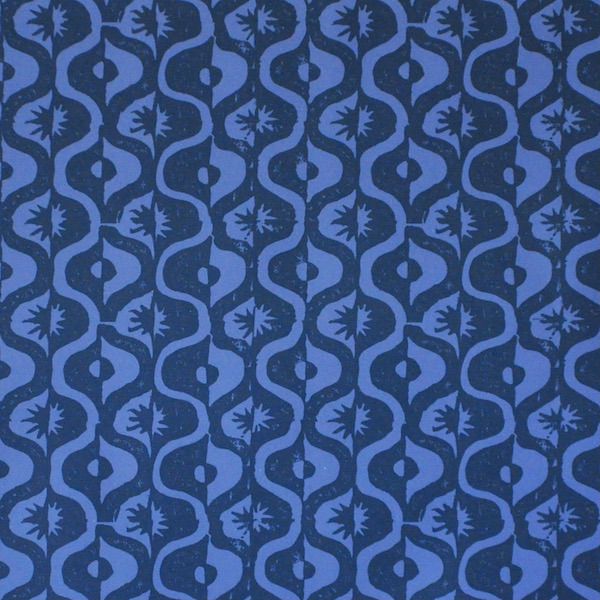

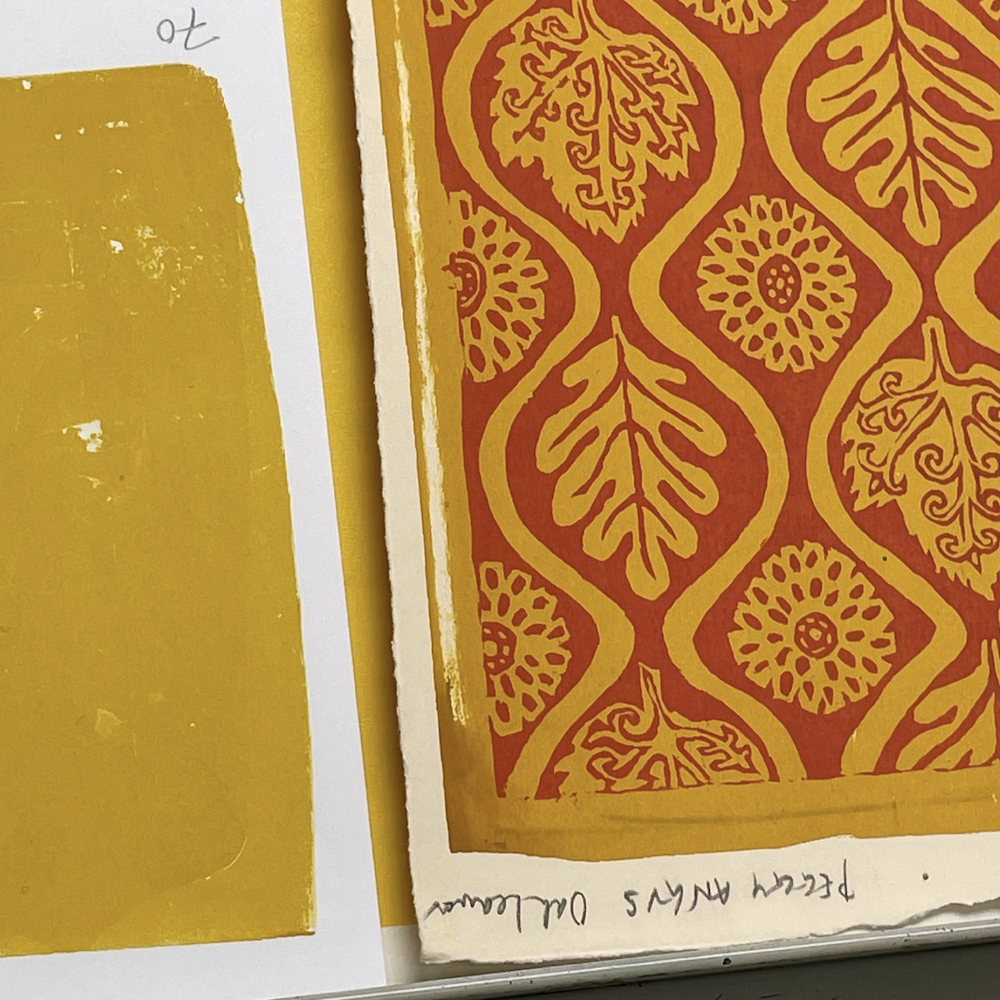

Unsurprisingly then, her own creative interests moved from easel painting to decorative art and design and it was here that her genius lay. She had great success early on with designing tiles for industry — tiles of fairly simple elements that could be repeated singly or together in an unlimited array of combinations and permutations. But the designs for which she is best known are her hand-block-printed wallpapers which she began printing as commercial enterprise in the late fifties. It was a laborious process for which she immediately enlisted the help of her daughter Victoria and anyone else who happened to be around.

Rolls of plain lining paper were painted with ordinary wall emulsion in a background colour and hung to dry on a complicated system of bits of plastic drainpipe. They were then overprinted with emulsion in a different colour using the lino blocks that Peggy Angus designed and cut herself. The designs were sometimes geometrical and minimalist and of their mid-twentieth century moment, but more usually they were extraordinarily vivid and exuberant figurative designs with a strong medieval influence, definitely centred in the art studied in the first two years of the art syllabus she devised: magic art that celebrates life in all its burgeoning variety. The designs incorporate birds and beasts, twining vines and ears of wheat; leaves and flowers; the sun and other stars. The scale of the designs was bold (we were astonished when we saw the originals after years of seeing them only in reproduction) and so were the colourways. But the effect of the wallpapered rooms was actually surprisingly gentle and liveable, the infinite variety and modulation created by the hand-blocking process making an ideal texture to set off paintings, far more sympathetic to the eye than the relentless regularity produced by a machine.

The wallpaper designs were often specific to the location of the house they were made for, or the occupations or interests of its inhabitants. They were designed and printed to order, in colourways specific to that job. As is appropriate to her spirit of prodigality, only tantalising traces of these bespoke interiors survive. All were in private houses. Many were over the course of time redecorated, perhaps by people who didn’t understand what a treasure they possessed. Very few were ever documented. There are a few photographs, often in black and white, and an archive of samples, and the original lino blocks themselves. If you are searching for images and information, it is difficult to find. Peggy’s student and friend Carolyn Trant wrote a wonderful biography, Art For Life, but it was published as a (very) limited edition and if you find a copy for sale now it could not be purchased without taking out a mortgage. We must thank Hughes Hall in Cambridge for lending us their rare copy, complete with hand-printed samples. There was an exhibition at the Towner Gallery in 2014 with examples of the wallpapers, and the accompanying catalogue by James Russell is a valuable source of images and information, but it too is hard to come by now and very expensive.

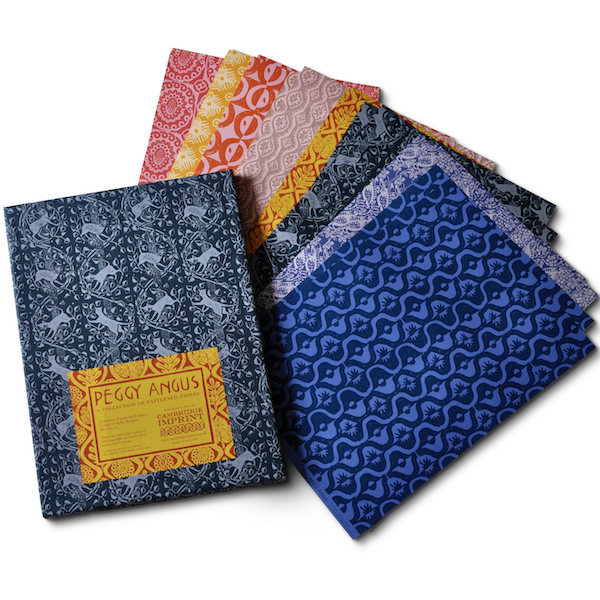

Happily, it is possible to purchase some of Peggy Angus’s designs for interior decorating: for several years Blithfield have produced wallpapers and upholstery fabrics in some designs, and you can find these online. They are faithful reproductions except that the colour ways are on the whole more gently tasteful and pretty than the rich and unexpected combinations that she favoured. Working with her designs at a smaller scale, and for a totally different purpose, we have so enjoyed playing with colour in creating a collection of patterned papers that evokes some of the eccentricity of Peggy Angus’s design and colour sense for others who, like us of slender means, would nevertheless like an opportunity to bring her sensibility into our own homes and derive inspiration from it. This boxed set of 24 sheets of paper, 3 of each of eight designs, can now be found on our website, and larger sheets of each paper are also available to buy singly. We hope you’ll have as much fun playing with the papers as we did making them.

It was terribly difficult to make a decision about which of Peggy Angus’s designs to choose and we hope that we might be adding to the range in the future. It was extraordinarily stimulating to spend time in her company, so to speak, even at this great distance. (She died in 1993 at the age of 89.) Perhaps in real life a little of her went a long way. But it is clear that she had the effect of stirring up everyone around her to roll up their sleeves, plunge in, and make things. When we mentioned at the end of our last newsletter that we were working on her archive, we received quite a number of reminiscences from old pupils who remembered her teaching vividly. Thank you very much. We would love to hear more, so if you have one please get in touch. And if anyone actually knows the Story Of The Teeny, Tiny Woman which Peggy is apparently so animatedly telling in the first photograph of her above, we are intrigued and would so like to hear it.