22 Jun On-Again, Off-Again

Summer seemed at last to be in full swing there for a little while. The glorious sunshine blazed as important foreign leaders hobnobbed in person, barefoot on a beach in Cornwall, eating what appeared to be genuinely delicious food and soaking in the ultra-violent rays. All creatures everywhere emerged from their hiding places and rushed about, attempting to reproduce as quickly as possible. There was a universal feeling of make hay while the sun shines and gather ye rosebuds while ye may. Right now though that seems to have been suspended pending further announcements. The virus is surging (or perhaps just gently welling), the lifting of the final restrictions has been suspended and we’re all holding our breath while dark clouds once again cover the sun. Perhaps in a time of plague all events can be read as signs and portents? Anyway, here at Cambridge Imprint we’re keeping our heads down and continuing with the rosebud gathering and hay-making in spite of the weather, literal and metaphorical.

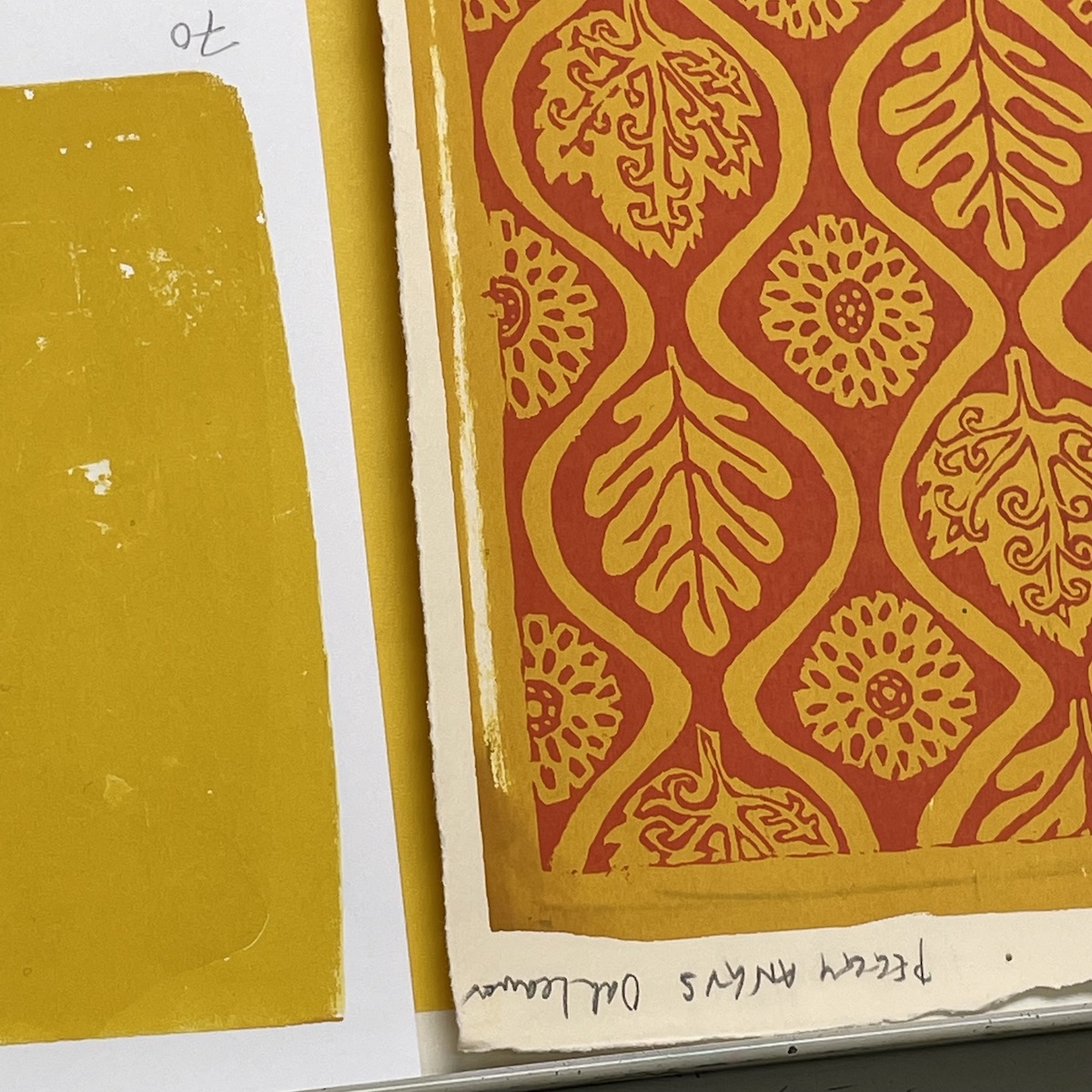

We spent part of the winter and all of the spring on a really delicious project. Peggy Angus was a pattern maker of the mid-twentieth century whom we particularly admire. Contemporary and friend of Eric Ravilious and Edward Bawden, independent spirit and inspired teacher, she was a painter who really found her element when she began to design in the fifties, first collaborating with industry to create patterned tiles, with which she had a great success, and then later branching out on her own with wallpapers. Her wallpapers were linocuts hand-printed in emulsion on lining paper. The few examples that survive are hidden away in private houses. Publications about her are few and it’s hard to obtain copies. I’m sure we’re not the only people who wished for her designs to be more freely accessible in some form.

So we were very pleased when Peggy’s granddaughter Emma Gibson asked us if we might be interested in reproducing some of Peggy’s designs as patterned papers. The original lino-cut printing blocks still exist. The scale is in all cases gloriously bold, as befits a pattern for wallpaper. We spent several months playing with various designs. We wanted to reduce the scale to something suitable for bookbinding and other more modest projects than wallpapering a whole room. On the other hand we wanted to recreate suitably vivid colour ways of the kind Peggy favoured.

After a satisfying time messing around with these extremely pleasing patterns, and in consultation with Emma, we settled on a set of eight designs which are being printed this month and will be available for sale towards the end of the summer. One is an early tile pattern and the other seven are wallpaper designs. Between them they show off the full range of her inventiveness, from her early clean mid-century modern patterns to the later bucolic, naive, figurative designs with their medieval and folk-art influences. We’ll write a much longer letter about Peggy Angus and her patterns when the papers are ready. Watch this space.

The Peggy Angus papers are the most ambitious of several projects that we’re urging on to fruition right now. Hopeful but not absolutely certain that there won’t be further bumps along the road to the pandemic being over, we’re working as hard as we can while conditions are somewhat easier to hatch all these long-incubated eggs. We do have a couple of new hatchlings already arrived.

Here you can see our patterned paper lampshades in three new colours – bright blue, dusk blue-grey, and a cool pink — which join our existing shades in earth red and bawden green. We have managed once again to source turned wooden lamp bases to match. They’re made in England, with brass lamp-holders and antique-gold flex, and they’re made of beech which we have painted and waxed in colours that coordinate with the shades. Unfortunately, the price of the lamp bases has doubled in the past few months and they can no longer be considered the bargain they once were. Also, we have very few of them. But the price of the fine yet robust paper shades, made for us from our patterned card by Samarkand Design, is unchanged.

We also have some new birch trays which have arrived after a long and anxious journey from the island of Öland off the coast of Sweden where they are made for us. The combination of Brexit and the pestilence has created some sort of perfect storm of shipping calamity, it seems. The giant container ship that ran aground in the Suez Canal in March and created a hideous planet-sized traffic jam further contributed to the pandemonium. One of the freight coordinators we sometimes deal with, usually given to extravagant assurances about making our lives much, much easier, sent an email recently in which the word ‘diabolical’ was used and there may have been a veiled reference to piracy. Not having to deal with this sort of thing very much is yet another advantage to having most of our products made here. However, we haven’t found anyone in the UK yet who can make these trays for us and we are delighted to have these new arrivals after their long wanderings to and fro across the continent from depot to depot, in search of someone who understands the paperwork. This is the new round birch tray in the Animalcules pattern, printed in a soft powder blue. The colour is curiously difficult to photograph, but is in real life somewhere between the two shades you see here.

Right – we must sign off, reapply nose to grindstone, seize the day and what-have-you. No summer holiday for us, which is no hardship as we’re all in the same boat in that regard it seems. A recent train trip to London to visit our printer in Bethnal Green persuaded us, if persuasion were necessary, that travel of a more ambitious kind is not to be thought of. The blazing heat led to points failure halfway back to Cambridge and the dread replacement bus service. Dutifully, everyone who had been on the train lined up in a giant socially-distanced queue in the car park in the pitiless sun. All wearing our masks outdoors because, I suppose, we felt that the car park was serving as a proxy for the station platform, and therefore it was the right thing to do, socially speaking: when on public transport, must wear mask. An anxious young man whose job it was to look after us and keep us under control trotted backwards and forwards handing out bottles of water, which seemed to me to be a covid-era gesture of solidarity and care for the potentially vulnerable. At last the bus arrived and small parties were allowed to embark one by one – no rush, no breaking of social distancing. But inexorably the bus filled until it was absolutely stuffed to the brim like a can of sardines, and in this state we set off on the forty-five minute journey to Cambridge. There wasn’t so much as a murmur of complaint or dissent. This experience filled me with love for my fellow citizens: the invariable effect, I find, of watching people so politely and sensibly queueing. But it was also all completely surreal. It confirmed for me the present moment: we none of us quite know what is going on, but we’re eager to do our bit, whatever strange and indeed contradictory form that might take.