17 Apr The Engines of Industry in a Time of Plague

We’re at the end of the third week of quarantine, and it’s just been announced that there will be at least three more weeks before there’s any change in the rules. The wheels here at Cambridge Imprint are still gently turning (thank you all for the orders which continue to arrive) but there is a distinct feeling of being in a backwater, while the action takes place elsewhere. In fact, just down the road.

It’s been moving to see on the news factories and laboratories all over the country repurposed for the production of scrubs, masks and ventilators, and for the carrying out of tests for the foul pestilence. Our neighbours in Cambridge seem all to be working through the night on new ventilator designs for Dyson or figuring out how to scale up their laboratory’s PCR testing capacity to quasi-industrial levels overnight. So far we haven’t managed to come up with a way in which decorative desk furniture and stationery can be drafted into the national effort. But we do feel satisfied that in the unlikely event of circumstances in which a really attractive and finely yet sturdily built box would save lives or contribute to national security, our supply chains would be rock solid.

Just as a surprising number of us have become armchair statisticians, so we are also suddenly hearing a lot about supply chain resilience and the dangers of globalisation from unexpected sources. These last topics are close to our hearts, but until recently it’s been hard to get a hearing. To talk about the erosion of local manufacturing and its perils has been, in our experience, to induce coma in one’s companion. Or perhaps it would be fairer to say that these processes seemed inevitable and unstoppable, and that the collective attitude was that it all just had to be accepted with a good grace. But now it turns out that most of the world’s protective gloves are made in Malaysia and most of the world’s swabs are made in Lombardy, and that in the current circumstances that’s a big problem for us all.

So we thought we would seize this opportunity to talk about the utter delight that a rich ecosystem of small local independent manufacturers is, from a design point of view, and our hope that this crisis might result in a sea change, a recognition that some small degree of protection from huge global financial currents could help to safeguard the high quality small-scale manufacturing that should surely always have been considered a national resource.

At Cambridge Imprint we make everything we possibly can in this country. There are so many things that make this a good idea. We want to control every detail of our products, in particular things like colour and texture, which can’t be communicated over long distances and where a language barrier really matters. We want to be sure that our things are made by people whose working conditions are safe and pleasant, and there’s really no way of being sure about that without visiting yourself. Crucially, understanding the circumstances of production is a spur to creativity. You find ways of doing things that suit the process instead of running against the grain. You see something being discarded and think: “Ooh. I could do something with that.”

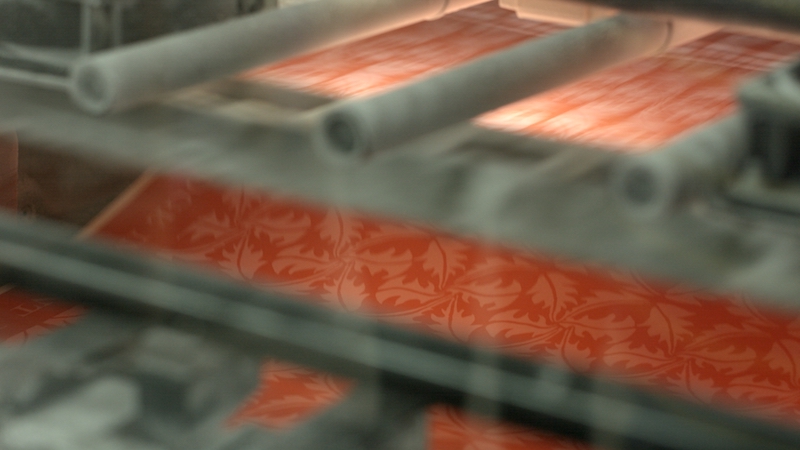

It’s only because we regularly visit our lovely printers to supervise colours that we really understood what vast quantities of paper usually have to be thrown away from the beginning of a print run as the colours are being adjusted: it’s perfectly good patterned paper, but the colour is not quite right. The desire to save this non-standard paper from the skip led to us unexpectedly getting into the origami business, and now (to our continuing astonishment) we sell thousands of origami kits every year. In fact a surprising number of our products have arisen from a need to find a use for waste products or spare capacity, or to create something that will fit into a strangely-shaped and otherwise unused space on a printing sheet.

We work with a great variety of small manufacturing businesses in this country. But for each one we find there are many that should exist, or once existed but do so no longer. It’s a challenge to find ribbon made here now: most is made in China. And there is no longer any domestic thread industry at all. We used to have document wallets with those lovely washer and string fastenings. But shortly after we made them, the person who attached the washers and strings for us went out of business, and he seems to have been the last person in the UK who was the master of that particular process. We’re not able to make address books (an ancient but effective technology) because no-one here can make the progressively cut-away alphabetical pages anymore: we would have to source ready-made ones from abroad, which we don’t want to do.

We work with a great variety of small manufacturing businesses in this country. These ladies are the incredibly skilled makers of our paper-covered boxes. They are part of a small manufacturing business that has been going for over 100 years. They make archiving boxes for museums all over the country and are in possession of a Royal Warrant, because, it turns out, the Queen needs a lot of special boxes too. They use tools and machinery that are as old as the business, but most of the building and covering is done by hand. There is no finer work of this sort to be found anywhere in the world.

We happened to be visiting at the end of January to discuss some new products we have been thinking about (ring-binders! pencils!) and took photographs of this huge stack of the ancient trays that jobs are carried around the factory in, and the vast library of bookcloths in great rolls of different colours that are used to make spines and hinges. The whole place fills us with the thrill of what might be possible.

On a visit a few years ago, we made this little film of the box makers in action which we then put in a cupboard and forgot about. We thought you might like to see it now, and join us in a fervent prayer that this factory and our whole delicate manufacturing ecosystem will weather this storm and be back in business before long. Not just that, in fact: that this disaster may turn out to be an opportunity to reinvigorate local networks and expertise that turn out to be an awfully good thing to have around.